Temporomandibular Joint Headache Facial Pain Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

Headache and temporomandibular pain are common complaints in patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMD). In the section below, we will present various aspects of TMD.

- Inhaltsverzeichnis

- What does the term “Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)” refer to?

- Anatomy of the Jaw Musculature and Temporomandibular Joints

- Risk Factors for Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

- Signs and Symptoms of Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

- Screening Questions for Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

- Diagnosing Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

- Video: Is jaw clicking dangerous?

- Treating Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

- Video: Tooth clenching and grinding

- Twelve Tips for TMD Self-Care

- Video: Arthrosis in the temporomandibular joint – What causes it?

- Video: Jaw exercises for TMD

- Video: Splint therapy for TMD

- TMD and Pain Chronicity

- Other Types of Oral, Jaw and Facial Pain

What does the term “Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)” refer to?

The term “temporomandibular disorders (TMD)” refers to a number of clinical issues that can concern the following somatic and psychosocial disorders1,2:

- pain in the area of the muscles of mastication and/or the temporomandibular joints that tends to be exacerbated during action (chewing, yawning, biting off)

- restrictions in the function of the mandible, especially when opening the jaw

- noises emitted from the temporomandibular joints (clicking, grinding) during movements of the mandible

- impaired quality of life and the psyche due to painful TMD (absenteeism, anxiety, depressive mood, etc.).

A current systematic review reports an incidence in the general population of around 3% for temporomandibular joint pain, 10% for pain in the masticatory muscles and 11% for joint bruits. For patients with TMD, the incidence of these three conditions is around 30%, 45% and 41% respectively.3,4

Sources:

1) De Leeuw R, Klasser GD (2013) Orofacial Pain. Quintessence Books // 2) Dworkin SF, Leresche L (1992) Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique // 3) Manfredini D et al. (2011): Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings // 4) Huang GJ et al. (2002): Risk factors for diagnostic subgroups of painful temporomandibular disorders (TMD)

to top

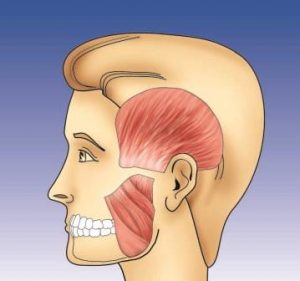

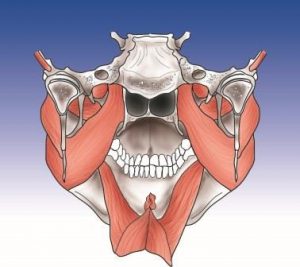

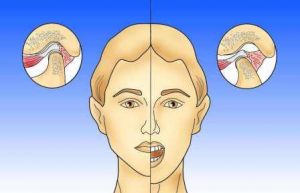

Anatomy of the Jaw Musculature and Temporomandibular Joints

Lateral view of the external masticatory muscles: temporalis muscle at the temple and masseter muscle in the area of the jaw

Internal masticatory muscles: medial pterygoid muscle, digastric muscle, lateral pterygoid muscle, myloid muscle

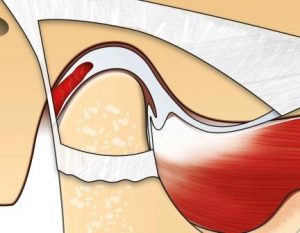

Posterior view of the temporomandibular joint

The healthy temporomandibular joint is enclosed by a fibrous capsule. The joint disc is located between the joint head and the joint socket. The lateral pterygoid muscle inserts toward the front.

As the jaws open, the joint head glides forward along with the joint disc.

Risk Factors for Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

- Pain: Frequently recurring or chronic pain is a typical characteristic of our Western civilization, with many people suffering from jaw pain, facial pain, headache, backache or other painful impairments. While in the past, illnesses were usually brief and intense and the patient either recovered or died of the illness, today our medical advancements offer effective help for nearly all acutely ill patients. In some cases, healing is only superficial; the disease only appears to be cured, and gradually transforms into a permanent painful impairment. This is a typical course of musculoskeletal disease. Acute pain due to accidents or inflammation can be treated successfully, but in many cases, recurrent stress and strain leads to chronic pain syndromes in the muscles and joints (masticatory muscle pain, temporomandibular joint pain, neck pain, etc.).

- Stress: Another typical characteristic of today’s society is chronic job- or family-related stress or stress due to other social factors. This uninterrupted stimulation of the autonomic nervous system targets not only the stomach or the nervous system. The teeth are a well-known “accessory” for processing pent-up tension by means of the masticatory muscles and the temporomandibular joint (grinding, clenching = “awake bruxism”). It may be true that stress has always been part of our culture, and that in the past, the survival of the fittest meant that humans had to cope with much more stress than they do today. However, in their daily food-gathering and quest for sheer survival, this stress was offset by physical activity.

- Exercise: The lack of exercise and physical activity rivals the lack of stress-coping options as one of today’s major health issues. These days, the average adult performs next to no physical activity when performing their work- or family-related duties. Mechanization is available to perform nearly any task requiring heavy labor.

- Nutrition: In addition, our eating habits do not take these lifestyle changes into account. An unbalanced diet or overeating often lead to additional physical stress, especially for the musculoskeletal system (overweight, cardiovascular disorders, etc.).

- Hormones: Many studies have also proven that hormonal factors may play a key role in the development of pain and increased sensitivity to pain (for example in the temporomandibular joint and masticatory muscles).

- Sleep: Another important risk factor for pain is sleep disorders. The inability to fall asleep or sleep through or early waking are widespread symptoms of insomnia, the most common sleep disorder. If we fail to experience deep-sleep phases and are frequently aroused, our muscles are unable to relax properly at night and are prone to increased activity. Tense masticatory muscles and headache in the morning (grinding and clenching at night = sleep bruxism) are common symptoms. Improving sleep quality through better sleep hygiene or medication, for example, can help reduce bruxism and tension.

- Occlusion: When it comes to the mouth, these problems are joined by the frequent need for treatment ensuing from extraction, jaw malformation, tooth decay or periodontal disease. Therapeutic interventions such as orthodontics, fillings or dentures thus lead to increasingly greater use of the natural adaptability of the tissue involved in the entire head region.

A whole range of risk factors can now lead to an increasing imbalance in the interaction between soft and hard structures in the head region. The muscles become tense and painful, the teeth become sensitive or excessively worn down, and the temporomandibular joint starts to click or hurts when it moves. There is wide variation in the individual propensity to contract these symptoms, however, and it is associated with both genetic factors and age, sex and nutritional factors.

Sources:

1) Huang GJ et al. (2008) Age and third molar extraction as risk factors for temporomandibular disorder // 2) Huang GJ et al. (2002) Risk factors for diagnostic subgroups of painful temporomandibular disorders (TMD) // 3) Fillingim RB et al. (2011) Potential psychosocial risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study // 4) Manfredini D et al. (2011) Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings // 5) Manfredini D et a. (2011) Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings // 6) Marklund S et al. (2010) Risk factors associated with incidence and persistence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders // 7) Michelotti A, et al. (2010) Oral parafunctions as risk factors for diagnostic TMD subgroups.

Signs and Symptoms of Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

Symptoms are complaints reported by the patient, such as “facial pain on the right”. Clinical signs are observed by the dentist during the examination. These may include areas of the muscles that are sensitive to touch (trigger points) in the area of the face or in the painful area. Common symptoms of TMD include pain in the jaw, masticatory muscles or temporomandibular joint, headache, clicking or grinding in the temporomandibular joint, tinnitus, as well as pain in structures that are not primarily affected, such as the teeth. The fact that the pain often does not occur where it originates is confusing for both the patient and the physician. For example, in the case of “referred pain”, trigger points in certain areas cause pain in other areas. Below is a list of symptoms/signs of TMD and symptoms and risk factors that should be taken into consideration when diagnosing TMD:

List of TMD symptoms1-21:

Teeth

- Awake bruxism, i.e. grinding or clenching during the day

- Toothache

- Bite that no longer fits after a dental treatment (malocclusion).

Temporomandibular joint

- Painful temporomandibular joint

- Clicking in the temporomandibular joint

- Grinding in the temporomandibular joint

Jaw and mouth

- Painful jaw

- Mouth does not open properly

- Chewing on one side

- Tension of the jaw during chewing

- Numbness in the jaw

- Head and face

- Headache

- Facial pain

- Numbness in the face

- Sensitive hair

Ears

- Auditory noises

- Earache

- Dizziness

Eyes

- Pain behind the eyes

- Sensitivity to light

- Impaired vision

- Throat and neck

- Difficulty swallowing (globus sensation)

- Sore throat

- Accident with injury to the jaw

- Whiplash

- General anesthesia with long intubation

- Mouth open for an extensive period during dental treatment

Body

- Neck pain

- Shoulder pain

- Back pain

- Numbness in the arms or legs

Sleep

- Sleep bruxism, i.e. grinding or clenching the teeth at night

- Insomnia: difficulty falling asleep or sleeping through the night or waking early

- Snoring

- Sleep apnea

- Daytime fatigue

Psychosocial factors

- Stress at school/on the job/in the family

- Restlessness

- Brooding

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Past traumatic experience

Sources:

1) Wright EF (2014) Manual of Temporomandibular Disorders. Wiley Blackwell De Leeuw R, Klasser GD (2013) Orofacial Pain. Quintessence Books // 2) Dworkin SF, Leresche L (1992) Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique // 3) Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Greenspan JD et al. (2011) Potential psychosocial risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study // 4) Huang GJ, Drangsholt MT, Rue TC et al. (2008) Age and third molar extraction as risk factors for temporomandibular disorder // 5) Huang GJ, Leresche L, Critchlow CW et al. (2002) Risk factors for diagnostic subgroups of painful temporomandibular disorders (TMD). // 7) Kindler S, Samietz S, Houshmand M et al. (2012) Depressive and anxiety symptoms as risk factors for temporomandibular joint pain: a prospective cohort study in the general population // 9) Magalhaes BG, De-Sousa ST, De Mello VV et al. (2014) Risk factors for temporomandibular disorder: binary logistic regression analysis // 10) Manfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L, Winocur E et al. (2011) Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings. // 11) Manfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L, Winocur E et al. (2011) Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings // 12) Marklund S, Wanman A (2010) Risk factors associated with incidence and persistence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders // 13) Michelotti A, Cioffi I, Festa P et al. (2010) Oral parafunctions as risk factors for diagnostic TMD subgroups // 15) Ohrbach R, Fillingim RB, Mulkey F et al. (2011) Clinical findings and pain symptoms as potential risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study // 16) Okeson JP (2013) Management of Temporomandibular Disorders. Elsevier // 17) Peck CC, Goulet JP, Lobbezoo F et al. (2014) Expanding the taxonomy of the diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders // 18) Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E et al. (2014) Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Groupdagger // 19) Schiffman EL, Velly AM, Look JO et al // (2014) Effects of four treatment strategies for temporomandibular joint closed lock // 20) Slade GD, Diatchenko L, Ohrbach R et al. (2008) Orthodontic Treatment, Genetic Factors and Risk of Temporomandibular Disorder // 21) Smith SB, Maixner DW, Greenspan JD et al. (2011) Potential genetic risk factors for chronic TMD: genetic associations from the OPPERA case control study.

Screening Questions for Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

If you answer “yes” to one or more of the following questions, the likelihood is very high that you have typical TMD, in other words, with muscular and/or joint-related pain (myofascial pain/arthralgia according to the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD).1,2

- Do you have pain at least once a week when you open your mouth or chew?

- Do you have pain in the left or right side of your face or in both sides?

- During the past week, did you have pain in your temple, face or temporomandibular joint at least once?

Sources:

1) Nilsson IM et al. (2009): The reliability and validity of self-reported temporomandibular pain in adolescents // 2) Reissmann DR et al. (2009): An abbreviated version of the RDC/TMD.

Diagnosing Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

In order to diagnose TMD, two things must be in place: First, the patient must report a symptom, such as facial pain. Secondly, the dentist must observe a fitting clinical sign, such as one or more points in the masticatory muscles that are sensitive to pressure and can trigger exactly this facial pain. In this case, the diagnosis would be as follows: myalgia of the muscles of mastication.1

To evaluate/diagnose TMD and for differential diagnosis of other orofacial pain syndromes, depending on the severity and complexity, the dentist will perform the following steps in order to make somatic diagnoses and suspected psychosocial diagnoses1-4:

- Patient history: an in-depth consultation using a standardized questionnaire and a pain drawing

- Somatic examination of the head region: the evaluation of teeth, gums, jaw, mucosa, lymph nodes, occlusion, head and jaw movements, masticatory and head muscles, temporomandibular joints and neurological signs

- Imaging: A panoramic radiograph, individual radiographs or three-dimensional imaging of the maxilla and/or mandible may sometimes be a good way to rule out other causes for the pain.

- Psychosocial screening: The evaluation of pain-related disability as well as of anxiety, depression and other psychic factors using psychometric questionnaires is indispensable for obtaining a complete picture of the patient.

- Unclear or complex jaw or facial pain: In the case of unclear or complex disease presentations, additional laboratory tests, imaging, radiological and/or psychological testing may be used and specialists from other disciplines may be consulted.

- Electronic diagnostic methods: Electronic measurement of joint inclination, electromyography, electrokinesiography, electrosonography, etc. may be worthwhile for informing and motivating the patient. However, there is no scientific evidence to support their usefulness in diagnosing TMD.5-7

Sources:

1) Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E et al. (2014) Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group // 2) Peck CC et al. (2014) Expanding the taxonomy of the diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders // 3) Wright EF (2014) Manual of Temporomandibular Disorders. Wiley Blackwell // 4) De Leeuw R, Klasser GD (2013) Orofacial Pain. Quintessence Books // 5) Okeson JP (2013) Management of Temporomandibular Disorders-Elsevier // 6) Greene CS: Managing the care of patients with temporomandibular disorders: a new guideline for care (2010) // 7) Tinnemann P et al. (2010): Zahnmedizinische Indikationen für standardisierte Verfahren der instrumentellen Funktionsanalyse.

Video: Is jaw clicking dangerous?

Treating Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

The basic idea for treating TMD involves careful use of reversible measures. Depending on the severity of the disorder, scientifically recognized evidence-based therapy concepts are individually and incrementally matched to the patient’s needs.1-7

- The first important step to positively influencing the disorder involves informing the patient about diagnoses and circumstances of the disorder.

- In many cases, tips for self-care, such as soft food, massage exercises, application of heat or cold, relaxation exercises, breathing exercises, self-observation and “lips together, teeth apart” can be helpful. Biofeedback and stress management are also helpful techniques that the patient can learn. Aerobic endurance training, such as jogging, the use of a cross-trainer, or swimming, are effective for treating TMD and a number of other painful muscle disorders (see Twelve Tips for TMD Self-Care).

- Dentists often prescribe a hard occlusal splint, which in many cases relieves the symptoms and alleviates pressure on the temporomandibular joint.

- Physiotherapy interventions and daily exercises can help reduce muscle tension and pain.

- In selected cases, pain-relievers, anti-inflammatories, muscle relaxants or sleep medication may be indicated to counteract chronic pain processes and improve quality of life.

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) may substantially reduce pain and relax muscles.

- Acupuncture, infiltrations with procaine and trigger point dry needling are currently being discussed as a treatment for TMD along with their capacity to provide long-lasting relief.

- Extensive oral rehabilitation, orthodontic or surgical interventions should only be used if strictly indicated and after providing the patient with in-depth information and considering the advantages and disadvantages.

Sources:

1) Greene CS (2010): Managing the care of patients with temporomandibular disorders: a new guideline for care // 2) Al-ani MZ et al.: Stabilisation splint therapy for temporomandibular pain dysfunction syndrome (2004) // 3) Schindler HJ et al.: Therapie bei Schmerzen der Kaumuskulatur (2007) // 4) Hugger A et al.: Therapie bei Arthralgie der Kiefergelenke (2007) // 5) Tinnemann P et al.: Zahnmedizinische Indikationen für standardisierte Verfahren der instrumentellen Funktionsanalyse(2010) // 6) Türp JC: Über-, Unter- und Fehlversorgung in der Funktionsdiagnostik und -therapie (2001) // 7) List T et al.: Management of TMD: evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analysis (2010)

Video: Tooth clenching and grinding

Twelve Tips for TMD Self-Care

Your dentist has diagnosed you with temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD). “T” stands for “temporo” (temple), “M” stands for “mandible” (lower jaw) and “D” stands for disorder. In most cases, the dysfunction in this area is caused by stress and strain.

We use this system for a number of activities, such as speaking, chewing, drinking, yawning, laughing and kissing… When we are not performing these activities, we allow the muscles of mastication (chewing) and the temporomandibular joints time to relax. However, many people have developed habits that do not allow the muscles and joints any time to regenerate. You can use the self-care measures below to considerably relieve the pain associated with TMD:

1. Exercise: Exercise is nature’s best medicine and is recommended by all medical associations (“light aerobic endurance training”). During exercise, important substances are released in the body that provide pain relief and are mood-enhancing. In consultation with your physicians/physical therapists, make sure that the amount of exercises is right for your level of fitness.

2. Relaxation: Doing progressive muscle relaxation according to Jacobson once or twice a day reduces the tension in your muscles and your pain by one-third. If you find it difficult to do the full version, start with the brief version that takes approximately 5 minutes (CD Progressive Muscle Relaxation According to Jacobson). A number of other relaxation techniques are available that may bring about similar effects.

3. Tooth contacts: Pay attention to your tooth contacts! Avoid clenching or grinding your teeth as well as tensing your tongue and facial muscles. Your teeth should only touch each other when you are swallowing and eating. Otherwise, the motto “Lips together, teeth apart” applies. The best mouth guard is an “air guard”. Blow air between your teeth, keeping them apart. As you do so, your tongue should rest on the gums in a relaxed manner directly behind the upper anterior teeth. Be aware of this, especially at work, while you are participating in sports, while you are driving or doing yardwork and while you are working in the kitchen.

4. Jaw exercises: Performing jaw exercises for 3 minutes in the morning and the evening is a very helpful way to stretch the muscles and dissolve trigger points (see Jaw Exercises information sheet). If the temporomandibular joints are also painful and inflamed, however, it is better to avoid this exercise.

5. Body and head posture: The position of the head appears to play an important role in TMD. Be sure to keep your head and shoulders straight. This is especially important when performing extended activities at the computer or when talking on the telephone (see Posture Training information sheet).

6. Physical therapy: Applying heat and cold alternatively can relax the muscles and relieve pain, especially prior to performing jaw exercises. Most patients prefer heat.

Apply heat for 20 minutes 2 to 4 times a day. Wrap a warm damp washcloth around a hot water bottle filled with hot water or a heat patch.

Then place a washcloth filled with ice cubes on the same areas for approximately 5 minutes until the area feels numb. If applying ice exacerbates the pain, shorten the application time. Only apply ice if it improves the situation.

Heat patches on the neck or back muscles provide heat that lasts for around 8 hours and are very helpful.

7. Massage: Massage your masticatory muscles if it makes them feel better. Use your index, middle and ring fingers to knead the skin. The pressure should feel slightly painful.

8. Soft food: Eat soft food. Cut up food in small pieces to prevent the jaw from having to open widely. Chew evenly on both sides.

9. Protect the muscles: Avoid consuming coffee and nicotine, because this causes the muscles to tense up and disrupts sleep. Caffeine-like substances are also found in teas, carbonated beverages and chocolate.

10. Pay attention to your sleep hygiene. Avoid sleeping positions that cause tension in your neck and jaw, such as sleeping on your stomach. Also avoid having lively conversations or doing sports in the late evening and do not drink coffee or alcohol before going to bed. This can worsen sleep quality, increase muscle tension during the night and exacerbate the pain (see Sleep Hygiene information sheet).

11. Avoid opening your jaw wide for long periods: Avoid keeping your mouth open for long periods, for instance, during extensive dental treatment or while under general anesthesia. Singing or playing an instrument for long periods sometimes leads to extreme muscle tension and should be reduced. If it is not possible to avoid these activities, it is sometimes helpful to perform exercises, stretch or take medication before you start.

12. Medication: Pain relief ointments or patches applied to the painful areas can sometimes be helpful. Taking paracetamol, ibuprofen or diclofenac for a brief period is sometimes indicated, but should be accompanied by stomach-protective substances. Avoid combined pain preparations, especially if they contain caffeine or codeine. Taking these classic pain relievers for longer periods can lead to organ damage/addiction and can even cause more pain (drug-induced headache). In this case, it is better to use more suitable pain relievers that cause little or no organic or psychic changes and to use the medication under medical supervision.

Your dentist will usually recommend other individualized therapeutic interventions such as wearing an occlusal splint at night or for certain periods during the day, as well as physical therapy, medication or psychological support (see discharge letter). The use of these interventions depends on a number of factors including the exact diagnosis, the degree of pain chronicity and the age/sex of the patient. Some patients do not respond to the above-mentioned interventions. The following factors may be responsible for the lack of response:

- Poor implementation of the recommendations on the part of the patient. There is a wide range of reasons for this and they should be discussed with the attending physician/dentist.

- A further physical, psychological or psychiatric condition is in place that has not been diagnosed. In this case, additional multidisciplinary diagnostics must be undertaken.

- Changes in the nervous system have caused the pain to become chronic. In this case, multimodal pain therapy by specialized doctors/centers in cooperation with your dentist is indicated.

Sources:

1) Wright EF (2014) Manual of Temporomandibular Disorders. Wiley Blackwell // 2) De Leeuw R, Klasser GD (2013) Orofacial Pain. Quintessence Books // 3) Okeson JP (2013) Management of Temporomandibular Disorders. Elsevier

Video: Arthrosis in the temporomandibular joint – What causes it?

Video: Jaw exercises for TMD

Video: Splint therapy for TMD

TMD and Pain Chronicity

Some 10% to 15% of patients with TMD develop chronic pain, especially if multiple risk factors are in place. For these patients, interdisciplinary measures may alleviate the symptoms and improve quality of life. This entails an individualized, patient-related combination of different treatment options.

The following characteristics are some important indications of chronic pain:

- Pain for longer than 6 months (“chronic pain”, “pain memory”)

- Multiple painful regions in the body (“multilocal pain”)

- Unwillingness on the part of the patient to modify his or her life circumstances and put into practice the attending physician/dentist’s recommendations such as relaxation exercises, aerobic endurance training, stress management, etc. (“poor coping”)

- Tendency to “somatize”, i.e. “translate” “stress” into physical symptoms

- Lack of understanding and support in the patient’s social and professional context (“poor bonding”).

- Pronounced pain-related psychosocial impairments such as absenteeism, anxiety and depressive tendencies

- Strong fixation and focus on the pain/occlusion and unwillingness/inability to focus one’s own attention on other things. For these patients, the term “occlusal dysesthesia” applies, consistent with “obsessive compulsive disorder”.

- The more chronic the pain, the more the patient suffers and the more the focus of treatment shifts to the psychosocial aspects of the disorder (“axis II”). For these patients, it may be worthwhile to use methods from psychological pain therapy, including pain coping techniques, cognitive behavior therapy, biofeedback and hypnosis.

Sources:

1) Flor H et al. (2011): Chronic Pain: an integrated Biobehavioral Approach // 2) Rollmann GB (2009): Perspectives of hypervigilance // 3) Palla S (1998): Myoarthropathien des Kausystems und orofaziale Schmerzen. Ätiopathogenese der Myoarthropathien // 4) Schwenk-von Heimendahl A (2010): Transkutane elektrische Nervenstimulation bei der Behandlung von kraniomandibulären Dysfunktionen

Other Types of Oral, Jaw and Facial Pain

TMD is only one of a number of possible reasons for oral, jaw and facial pain. This “orofacial pain” comprises pain that may occur in the region of the eyes, ears, nose, teeth, oral cavity, pharynx, cheeks and in front of the auricle of the ear1-3.

According to the American Academy of Orofacial Pain (AAOP), this orofacial pain is associated with “pain in the hard and soft tissue of the head, face and neck, as well as all intraoral structures”. In the view of the German Working Group for Orofacial Pain of the German Society for the Study of Pain (DGSS – Deutsche Gesellschaft zum Studium des Schmerzes), the terms “orofacial pain” and “facial pain” should be used synonymously in contrast to “craniofacial pain”, which includes the head region.

The causes, symptoms and location of orofacial pain vary widely. The following conditions may cause orofacial pain:

- Toothache (odontalgia)

- Facial pain and pain in the oral mucosa

- Myalgia of the masticatory and head muscles

- Painful temporomandibular joint

- Primary headache such as tension headaches, migraine or cluster headache

- Intermittent neuropathic pain such as trigeminal neuralgia

- Chronic neuropathic pain such as atypical odontalgia or burning mouth syndrome

- Herpes zoster (shingles)

- Fibromyalgia

- Borreliosis

- Injuries to or infections in the head region

- etc.

The treatment of orofacial pain is based on an unequivocal diagnosis and must be carried out by a specialist.

Sources:

1) De Leeuw R, Klasser GD (2013) Orofacial Pain. Quintessence Books // 2) Hugger A et al. (2006): Orofaziale Schmerzen. Der Schmerz // 3) Peck CC et al. (2014) Expanding the taxonomy of the diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders.